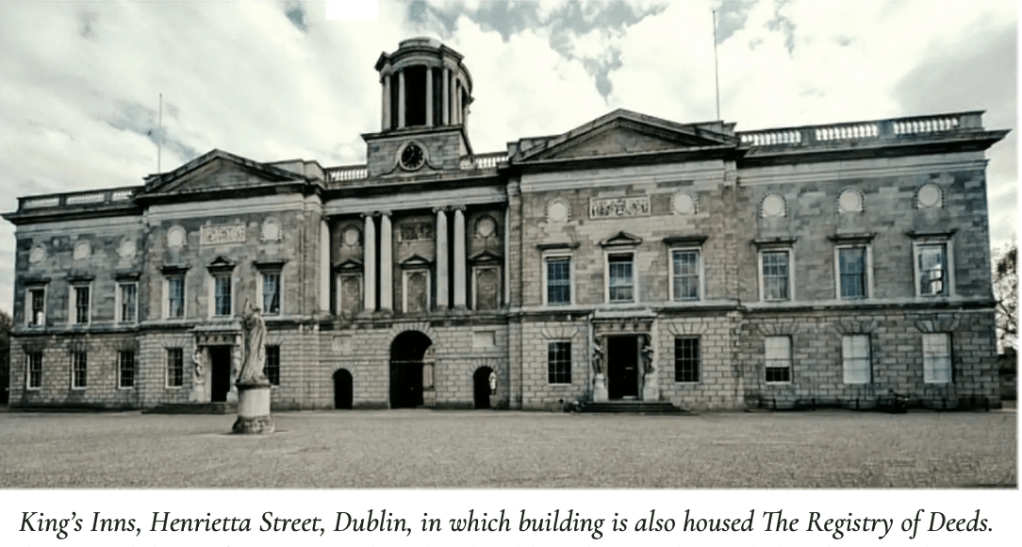

In earlier posts we have looked at a variety of sources related to the Kidd family. These documents include a surviving will. There are also family letters and newspaper entries. Additionally, there are the diaries of James Harshaw, who was the executor of the will. In this post I want to highlight another important source for 18th and early 19th century, The Registry of Deeds in Dublin. In its records there is another document that highlights what happened to one of the Kidd family farms after the court case.

Kings Inn Dublin

Photograph by “informatique” (2007); edited by Alison Kilpatrick (2021). Digital image online at Wikimedia Commons commonswikimedia.org (accessed 31st Jan. 2021); posted under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-SA 2.0 creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0.

Registry of Deeds Ireland

(https://timeline.ie/finding-your-irish-roots/registry-of-deeds/). The Registry of Deeds is the repository of the memorials of wills, land transactions, and other deeds recorded in Ireland. It was established in 1708, its earliest records date from 1709. Initially, many of the deeds are related to the large landowners and wealthy merchants. As time goes by, more small farmers, artisans, and merchants appear in their pages. However, registration was never obligatory, many transactions took place outside the system. Equally, given the way in which the memorials are indexed, finding a particular deed or individual is not easy. Nevertheless, this repository is particularly useful in Irish research. This is especially true if you think your ancestor owned property.

FamilySearch Online Resources

The body of the documents in the Registry of Deeds has become much more accessible in recent years as it is now available on FamilySearch at: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/185720 . There are many volumes and they are indexed, but only the grantor (the person who is selling or transferring the property) is included in the index. There are also land indexes which can be useful if you know where your ancestor lived.

Fortunately, I have been involved with an indexing project on the contents of the deeds for a number of years and have been learning to work my way around them. https://irishdeedsindex.net. I have discovered unexpected information on several branches of my family and have been able to delve back into the 18th century, always a goal in Irish genealogy.

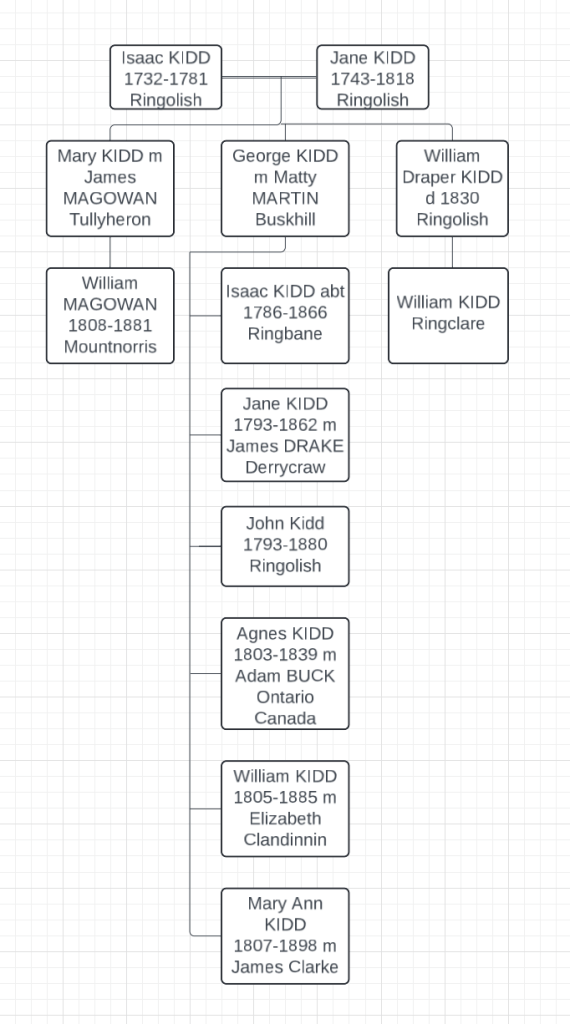

Family Tree

But, before we look at the Registry of Deeds information, here’s a reminder of the Kidd family involved in this convoluted series of legal proceedings and documents. In 1854 the Court of Chancery established that the proceeds of the sale of the farms in dispute would be divided between the descendants of the three children of Isaac and Jane Kidd as detailed left. George had six children so his share should have been divided in six. However Agnes (Nancy) Buck in Canada had died by 1839 and she is not mentioned in subsequent proceedings so her family may have been left out of the settlement. My hypothesis is that my great great grandfather William Kidd of Buskhill was the William, son of George Kidd. Why?

Because I know from his birth record that William was the son of George Kidd of Buskhill.

Because I have DNA matches with descendants of four of the five other children of George Kidd. However, I still have a niggling doubt that I may have jumped to a false conclusion. Nowhere in these documents has William been specifically recorded as William Kidd of Buskhill.

In Which the Kidd’s Long Legal Struggles are Finally Settled

As discussed in my last blog post https://archivedust.org/2024/09/29/examining-the-kidd-inheritance-dispute-through-james-harshaws-diary/ James Harshaw’s diary has been an invaluable resource in finding further information on the Kidd family’s legal disputes. Returning to his writings, I found this entry where he noted that on the 29th June 1860 he “met with William Magowan and William Kidd in Mr. Todd’s office where we agreed to settle the Kidd’s lawsuit and directed Mr. Todd it be wound up by distribution of the £920 by the sale of the Ringolish farm (occupied by John Kidd) and six and a half acres of the Ringbane Farm (occupied by Isaac Kidd)”. Given the long history of this legal dispute, I wondered if the sale might have been considered important enough to have been recorded in the Registry of Deeds.

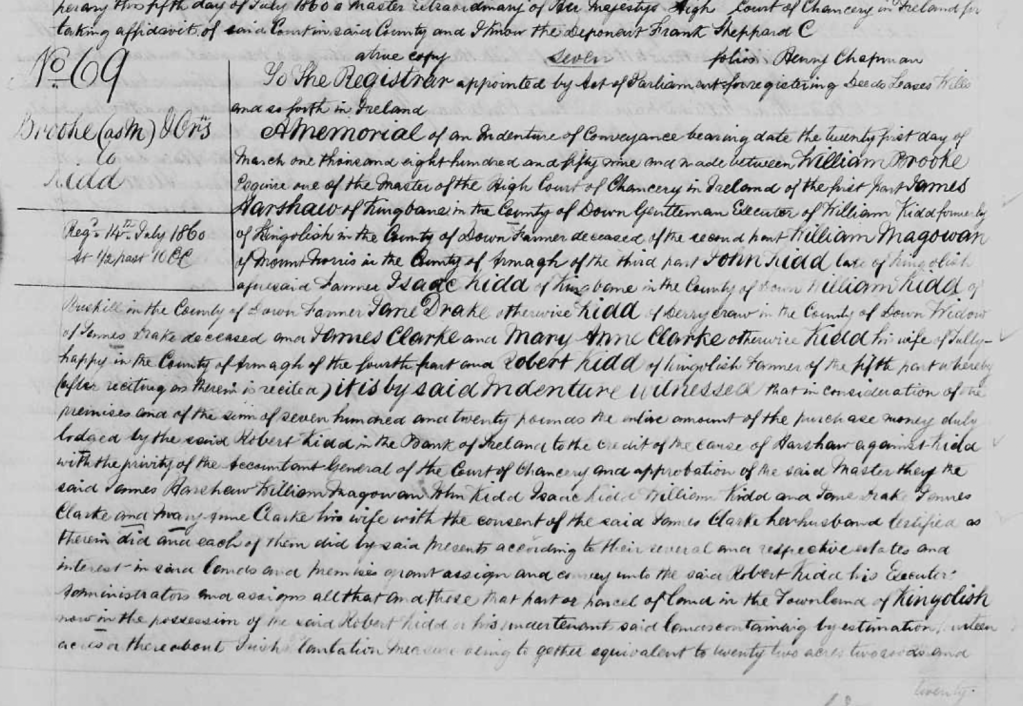

The Deed is Done

The point of entry to this transaction, if it was recorded, would be the name of the executor of the will, James Harshaw. And sure enough, there was a deed registered on 16th July 1860 with James Harshaw in his role as executor, in company with William Brooke, one of the Masters of the High Court of Chancery in Ireland, and William McGowan of Mountnorris, Co. Armagh, and with John Kidd late of Ringolish, Isaac Kidd of Ringbane, William Kidd of Buskhill, Jane Drake otherwise Kidd of Derrycraw, and Mary Ann Clarke otherwise Kidd of Tullyhappy, making over the lease of the Ringolish farm to Robert Kidd of Ringolish.

Gleanings

Do we learn anything new from this document? The answer is yes!

Yeah, This is my Ancestor William Kidd!

- Firstly and most importantly, it proves that the William Kidd involved in all these court proceedings was indeed my ancestor. For the first time William Kidd is specified as being of Buskhill. In 1860, when this sale took place, William Kidd’s daughter, my great grandmother, Agnes Kidd was 30 years old, still living at home, she would surely have been very aware of all the headache and financial difficulties caused by this ongoing dispute. perhaps she and her siblings benefited from the proceeds of the eventual sale.

Whatever Happened to John Kidd?

- Secondly, the deed says that John Kidd was late of Ringolish. This does not mean he was deceased, but rather that he was no longer living there. Through Isaac Kidd’s will in PRONI, I have been able to show that several of Isaac’s children were living in County Tyrone, while others were still in Donaghmore at the time of his death in 1866. But I have no information on John Kidd’s descendants. This is strange in that, as I also mentioned in a previous post, the same parcel of land in Ringolish occupied by John Kidd in 1854, 22 statute acres and change, that is further mentioned in this deed of 1860, is still occupied by a John Kidd in the 1864 Griffiths valuation.

The Invaluable James Harshaw

- Harshaw’s Diaries once again provides snippets of relevant information. On 16th November 1861 James Harshaw records that he visited Robert Kidd and his mother. On the 1st December he mentions again that he visited Robert Kidd and on the 7th December he notes that Robert died. On the 9th December he writes that he visited Mrs English Joe Kidd in consequence of the son Robert’s death and on 10th December he records that he attended Robert Kidd’s funeral. I know from others deeds from the 1830s that the English Joe Kidd family lived in Ringolish so there seems a strong possibility that this is the Robert Kidd who bought the disputed farm.

And Where is Draper Kidd’s son William?

- Thirdly, what happened to the other William Kidd, Draper Kidd’s son in this deed? This William Kidd (of Ringclare) and William Magowan were the ones who met at the lawyer’s office mentioned in James Harshaw’s notes in June 1860. They directed that the estate to the value of £920 be wound up. However, this deed of July 1850 only relates to the Ringolish farm which sold for £ 720. Did Draper Kidd’s son, William Kidd get the value of the Ringbane farm, the other £200?

Final Questions and Opportunities for Further Research

Did occupation of the farm in Ringolish return to John Kidd after Robert Kidd’s death? Is there more information to be found in the Registry of Deeds? Is this a different John Kidd in the Griffiths Valuation of 1864? Will I find a DNA connection to John Kidd? I have new edge pieces to the Kidd puzzle!

You must be logged in to post a comment.